I am sitting in the grass, on a comfortable rock next to the meandering Santa Cruz River in Rio Rico, Arizona. Nearby, a small but dedicated group of local residents work together to repair damage done to the rainwater harvesting features at the Guy Tobin Trailhead.

Previously, the Watershed Management Group, in partnership with the Friends of the Santa Cruz River, sent out a call to the people in and around Rio Rico to help develop rainwater harvesting and erosion control features at Guy Tobin Memorial Anza Trailhead. In a series of Saturday morning workshops (and I do mean WORK shops), which were financially supported by a grant from the EPA, students from the Rio Rico High School Interact Club and the Global Community Communications Starseed Schools for Teens and Children, as well as volunteers with the Anza Trail Coalition of Arizona and many local neighbors worked together to create rainwater harvesting features with the goal of improving storm-water quality and beautifying this tiny little park sandwiched between Rio Rico Dr. and the Santa Cruz River.

Previously, the Watershed Management Group, in partnership with the Friends of the Santa Cruz River, sent out a call to the people in and around Rio Rico to help develop rainwater harvesting and erosion control features at Guy Tobin Memorial Anza Trailhead. In a series of Saturday morning workshops (and I do mean WORK shops), which were financially supported by a grant from the EPA, students from the Rio Rico High School Interact Club and the Global Community Communications Starseed Schools for Teens and Children, as well as volunteers with the Anza Trail Coalition of Arizona and many local neighbors worked together to create rainwater harvesting features with the goal of improving storm-water quality and beautifying this tiny little park sandwiched between Rio Rico Dr. and the Santa Cruz River.

Starting at the top of this site, we created sunken basins and raised berms to direct and capture rainwater. We built erosion control structures like check dams, filtering strips, and a “Zuni bowl” to reduce erosion and keep sediment from the nearby road from going straight into the river with each rainstorm. We also planted native trees and shrubs inside the basins to create shade for people and habitat for our four-legged and winged animal friends.

Unfortunately, shortly after celebrating the completion of the watershed management project at Guy Tobin Trailhead, someone drove through all the puddles in the basins (during a big storm), destroying many of the new plants and damaging all the basins that had been so lovingly created.

So, here we are once again, enjoying each other’s company, shaking our heads about the people who made such a mess here, and acting positively in the face of growing concerns about global change that motivates us to care about one another and the environment—as we restore this little piece of the earth.

The term global change can be interpreted a number of ways, such as the Oxford Dictionary‘s definition:

If changes have world-wide repercussions, such as the release of carbon dioxide when a tropical rain forest is burnt, or involve a major portion of a global resource, such as water quantity and quality, or if a series of local changes accumulate to have an impact, as in accelerated soil erosion, these are global changes.

The Borderlands

We live in the borderlands of Southern Arizona, near the border crossing of Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora (Mexico). The “borders” of our little piece of the borderlands have been described in many ways, depending upon who is doing the describing. The Spaniards considered this region a part of the “Pimeria Alta”, and they chose that name because this was the northern portion of the lands occupied by the people they called “Pimas” and who called themselves variations on “O’odham”, which means “The People”. In modern times, the area is divided by a very unfriendly wall along the border that symbolizes to me the desperate attempt (by the old order) to hold back positive global change.

Many environmentalists see this area as being defined by the watershed of the Santa Cruz River, a region that has always been, and will always be, a naturally cohesive unit (since this little river blissfully ignores the border between Mexico and Arizona that it crosses twice in its course). But no matter who is defining the region, the area has been a dynamic, beautiful, and continuously bubbling melting pot of various cultures for hundreds of years.

Like every other point on the globe, this borderland area is a battleground for the clash between the old order, which I will call the mindset of “every man for himself” and the Divine New Order, which can be described as the mindset of “one God, one planetary family”.

Unlike many places in this world, the borderlands of the Santa Cruz Valley (traditionally called “The Palm of God’s Hand”) has a sufficiently intact cultural base to insure that people here will often take responsibility for planetary changes and join together to maintain, restore, and create community resources rather than wait for “the government” to do it. We have seen this in the practical and dynamic community response when budget cuts to public schools, as well as to county and state parks, threaten to undermine local resources. We also see this in the many local community groups that work to assist the “travelers” who are passing through on their way north—a mass migration of hunted and harassed people (on foot through the harsh desert terrain) searching for a better life for themselves and for their families. In this time of global pandemic, people all over the world are having to rely increasingly on their family, friends, and neighbors to survive. We are all forced, by current circumstances, to define our support systems for survival in ways that may ultimately be more sustainable to each bioregion.

I have heard many people comment that they feel something changes when they cross the invisible line into Santa Cruz County. The farther south you go, the further behind you leave the culture of the “spoiled and ugly Americans” and enter a world of many people who live too close to the edge to be spoiled and too connected to their homes and one another to be “ugly”.

How Global Changes Impact the Borderlands

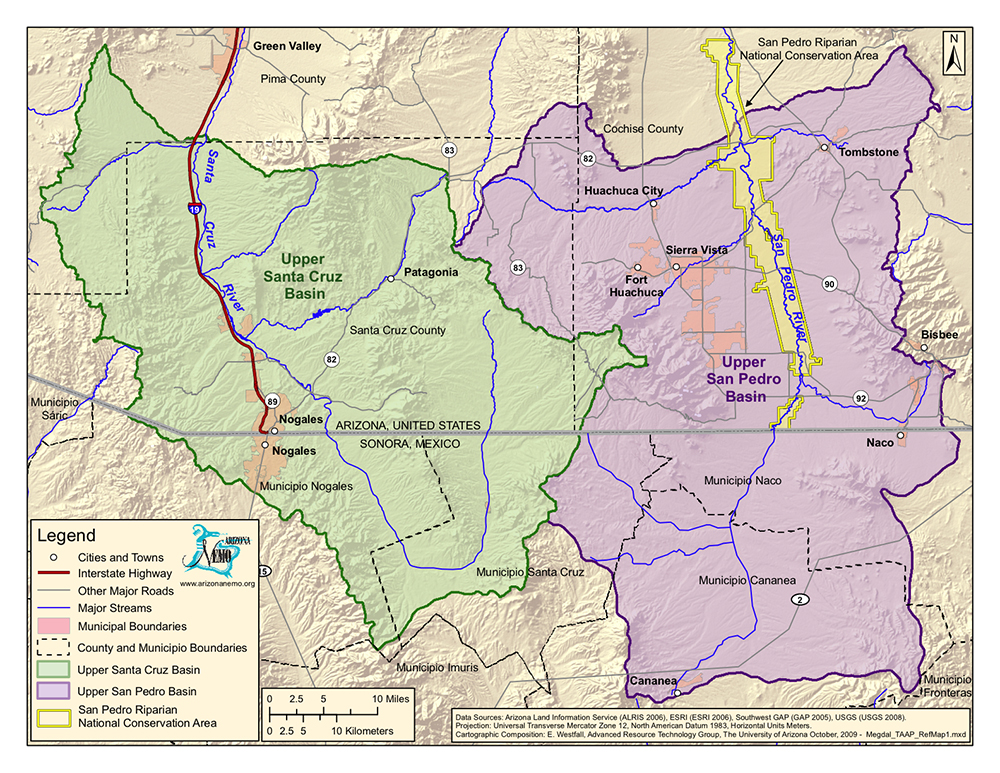

The swatch of the borderlands that is Santa Cruz County is a corridor, which is termed the “Upper Basin” of the Santa Cruz River. The Santa Cruz River starts out in San Rafael Valley (due east from Santa Cruz Valley) and meanders its way south into Mexico. It then takes a complete U-Turn and heads north again. So in the first stretch from the Canelo Hills in San Rafael Valley to Mexico, downstream is heading south. After it does its about face, downstream is heading north. Thus the southern end of the Santa Cruz River in Arizona is called the Upper Basin and it passes through the Middle and Lower Basins as it heads north into Tucson.

The Upper Basin of the Santa Cruz is flanked by mountain ranges that form the slopes of its surrounding watershed. We have the Tumacácori’s to the west and the San Cayetano’s and the Santa Rita’s to the east. The Patagonia Mountains east of the San Cayetano’s also provide slopes to gather water for the Santa Cruz River. Many people are working to preserve these mountains (as well as water quality and quantity and habitat for wildlife) by protecting them from mines that would undermine the carrying capacity of this bioregion to sustain its current population of human and wild life.

Carrying capacity is defined as: “Maximum population of a particular species that a given habitat can support over a given period of time.”[1]

Writer Peter Berg and ecologist Raymond Dasmann, both affiliated with the San Francisco environmental organization Planet Drum Foundation, popularized the term bioregion in the 1970s.

Every place on the Earth’s surface lies within a bioregion. One way to define the term is to say that a bioregion is a watershed area—the drainage basin of a stream or river. But this is not the only possible definition of “bioregion”.

More generally, a bioregion is a place that has commonalities of soil, surface water source, landforms, wildlife, climate and culture. The bioregionalism movement, which is increasingly active today, calls for defining areas based not on ecologically meaningless political boundaries but instead on natural geographic boundaries and characteristics. The border between Mexico and Arizona, for example, is a straight line that cuts straight across watersheds. A bioregional boundary would meander, tracing the dividing line between watersheds.

To live bioregionally is to live aware of the local ecology, steeped in the natural and indigenous history of the place and committed to making choices that help to balance human impacts with the carrying capacity of the environs.[2]

We are also a part of the Sky Islands bioregion, a chain of 55 mountain ranges that rise out of the valleys of Sonora Mexico and Southern Arizona, which is one of the most biodiverse regions of the world. We work to protect the mountains because water brings life and mountains bring water to the land.

There is so much that can be done to protect our bioregion from those who are circling around and trying to pounce on the available resources without really caring about the area, or the people in it, one bit.

Global changes are impacting the borderlands in the worldwide problem of contaminated drinking water. The surface waters in the Upper Santa Cruz Watershed near Nogales, Rio Rico, and Tubac, Arizona have been shown to have detectable levels of contaminants such as metals, pharmaceuticals, personal-care products, pesticides, flame retardants, etc.[3] Yet there have been few studies that monitor the presence of these contaminants in the drinking water supply.

"To live in the borderlands means to

Put chile in the borscht,

Eat whole wheat tortillas,

Speak Tex-Mex

with a Brooklyn accent;

Be stopped by la migra at the border checkpoints.

In the Borderlands

You are the battleground

Where enemies

are kin to each other.Excerpt from the poem

“To Live in the Borderlands”- by Gloria Anzaldua

The fact that effluent (delivered in a decrepit and failing pipe from Mexico to the treatment plant in Rio Rico) makes up a large portion of the surface water supply in the area suggests that people may be exposed to contaminants through their drinking water, but people who are not required to monitor their drinking water wells may not do so, due to the cost. One of the contaminant metals that has been identified in the water from time to time is cadmium, which is a known carcinogen and toxicant. When looking at the Santa Cruz Watershed, the areas of Nogales, Arizona and Sonora, Mexico are socioeconomically deprived. A review of Arizona Department of Health Services records provides evidence of disparities in adverse health and disease outcomes for children and pregnant women in the Nogales area.

In an article titled “High, Dry, and Up Against a Wall: Why Water and Food Justice are Key to Ending Border Conflicts” by Gary Nabhan, we learn:

. . . reports from Mexican border towns just south of Arizona and California say that 44% of the school students are living with the risk of hunger, and 82% of the households can be considered to be food insecure. . . And if you believe that the water and food injustice along our border is any less severe than that being suffered along the wall that cuts the Holy Lands in two, come and see us down in Southern Arizona, which barely ranks above Mississippi in its dismal levels of poverty and childhood food insecurity. If that’s not shocking enough for you, we’ll direct you on a tour to barrios just South of the wall where hunger and poverty are ramped up to a ferocity I’m certain you won’t be able to forget.

The good news is that there is a rising tide of global change that is tearing down the racial barriers, tearing down the walls that separate us, and breaking apart the world view that has gotten us into the mess we are in. It is time to stop allowing a small number of wealthy and powerfully evil people in the world to dictate a worst-case scenario for the planet just so they can get even richer and more powerful.

For at least 50 years, in early December there has been a Fiesta de Tumacácori event on the grounds of the Tumacácori Mission. All the various cultures of the borderlands come together at the Fiesta to celebrate that we are here and we are together. Every Christmas Eve, people from all around Southern Arizona come to the Mission to walk the grounds in the sacredness of the season. And now we have human-rights advocates of Global Community Communications Alliance and The University of Ascension Science and The Physics of Rebellion making our home just across the river from the Mission, living in an EcoVillage that is a prototype for people all over the world to come and learn how to live sustainably and in divine pattern.

For at least 50 years, in early December there has been a Fiesta de Tumacácori event on the grounds of the Tumacácori Mission. All the various cultures of the borderlands come together at the Fiesta to celebrate that we are here and we are together. Every Christmas Eve, people from all around Southern Arizona come to the Mission to walk the grounds in the sacredness of the season. And now we have human-rights advocates of Global Community Communications Alliance and The University of Ascension Science and The Physics of Rebellion making our home just across the river from the Mission, living in an EcoVillage that is a prototype for people all over the world to come and learn how to live sustainably and in divine pattern.

All over the world people are awakening to the realization that we must have positive and radical global change in order to survive, and the next step after that realization is to find the leaders who are equipped to foster that global change into positive directions. It is time, as Van of Urantia has been teaching for many years, for all people to unite and to begin to occupy their own minds and hearts with the SpiritualutionSM principles. And we can all start with the principle of one God, one planetary family. It matters not what name we use for “God”. When we know the Divine Creator, we treat everyone as our brothers and sisters. Everyone’s child is our child. And the Earth Mother Spirit is Mother of us all.

[1] From the glossary of the Tenth Edition of the book by G. Tyler Miller Jr., Living in the Environment

[2] Definition from the Forests Forever Web site: http://www.forestsforever.org/bioregions.html

[3] James Callegary of the USGS did a study of contaminants in the Santa Cruz River in 2009. They took samples from sites between Nogales and Tubac.