I was born in Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico in the early 1960s. Growing up, I did not know very much about the Bracero Program, nor did I ever hear the name Cesar Chávez. In Sonora, Mexico, up until the late ’90s, people referred to all documented (legal) or undocumented (illegal) immigrants who traveled to the U.S. as “braceros”. Two of my uncles worked as braceros in the United States. My mom’s brother was a bracero from 1956 to 1958 and earned enough money to purchase a record player and set himself up in a little business back home, where he was paid to bring his record player to provide music for parties. Another uncle worked in the U.S. from 1967 to 1968 and earned enough money to pay for his wedding and get started in life in Mexico.

The Bracero Program And Its Legacy

Since the early 1900s U.S. growers had grown rich by exploiting a series of disenfranchised workers in the fields. First there were the Chinese, then African Americans, then poor Caucasian Americans, Japanese, and Filipinos, and finally, starting in the 1940s, Mexicans. Today, millions of Mexican Americans trace their families’ roots in the U.S. to their fathers’ or grandfathers’ arrival as braceros.

The Bracero Program was created by executive order in 1942 because many growers argued that World War II would bring labor shortages to low-paying agricultural jobs. It grew out of a series of bi-lateral agreements between Mexico and the United States that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States to work for a short term, primarily in agricultural labor contracts. However, the Program lasted much longer than anticipated and brought 4.6 million Mexican guest workers to the United States between the years of 1942 to 1964.

This movement was a human rights movement from the very beginning.

–Dolores Huerta, close comrade of Cesar and Helen Chávez

In 1951, after nearly a decade in existence, concerns about production and the U.S. entry into the Korean conflict led Congress to formalize the Bracero Program with Public Law 78. Mexican nationals, desperate for work, were willing to take arduous jobs at wages scorned by most Americans. U.S. employers were supposed to hire braceros only in areas of certified domestic labor shortage and were not to use them as strikebreakers. In practice, employers ignored many of these rules, and Mexican and native workers suffered while growers benefited from plentiful, cheap labor.

Over the years, many braceros were able to secure green cards and legal residency, while others (known as “quits”) simply left the fields and headed for work in the cities. Between the 1940s and mid 1950s, farm wages dropped sharply compared to manufacturing wages, a result, in part, by the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society.

Unfortunately, the Bracero Program also had the unintended effect of encouraging illegal immigration when U.S. workers’ quotas were met. These new undocumented workers could not be employed “above the table” as part of the Program, leaving them open for exploitation. This resulted in the lowering of wages and not receiving the benefits that the Mexican government had negotiated to insure their documented workers’ well-being under the Bracero Program. This, in turn, had the effect of eroding support for the Program in the agricultural sector for the legal importation of workers from Mexico in favor of hiring undocumented immigrants to reduce overhead costs.

The advantages of hiring undocumented workers were that they were willing to work for lower wages, without health coverage, and, in many cases, without legal means to address abuses by the employers for fear of deportation. Nevertheless, conditions for the poor and unemployed in Mexico were such that illegal employment was attractive enough to motivate many to leave in search of work within the United States illegally, even if that directly competed with the documented workers within the Bracero Program, leading to its discontinuation in 1964.

Labor unions that tried to organize agricultural workers after World War II targeted the Bracero Program as a key impediment to improving the wages of domestic farm workers. These unions included the National Farm Laborers Union (NFLU)—later called the National Agricultural Workers Union (NAWU), headed by Ernesto Galarza—and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), AFL-CIO.

In 1956, labor organizer Ernesto Galarza’s book Stranger in Our Fields was published, drawing attention to the conditions experienced by braceros. The book begins with this statement from a worker: “In this camp, we have no names, we are called only by numbers.” The book concluded that workers were lied to, cheated, and “shamefully neglected.” The U.S. Department of Labor officer in charge of the Program, Lee G. Williams, described the Program as a system of “legalized slavery.”

Cesar's Story

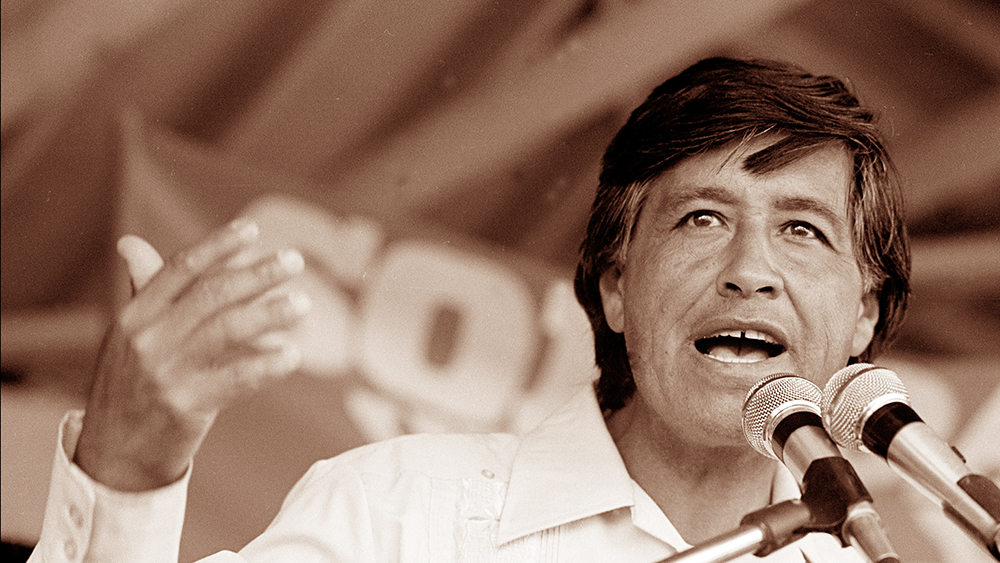

Cesar Chávez[i] had grown up working as a farm worker in the fields of California after his family lost their land in Arizona. He had very little education but was armed with high intelligence, a deep understanding of human beings, and an indomitable will.

During his tenure with the Community Service Organization, Cesar Chávez was given a grant by the AWOC to organize in Oxnard, California, which culminated in a protest of domestic U.S. agricultural workers of the U.S. Department of Labor’s administration of the Bracero Program. In January 1961, in an effort to publicize the effects of bracero labor on labor standards, the AWOC led a strike of lettuce workers at eighteen farms in the Imperial Valley, an agricultural region on the California-Mexico border and a major destination for braceros.

During his tenure with the Community Service Organization, Cesar Chávez was given a grant by the AWOC to organize in Oxnard, California, which culminated in a protest of domestic U.S. agricultural workers of the U.S. Department of Labor’s administration of the Bracero Program. In January 1961, in an effort to publicize the effects of bracero labor on labor standards, the AWOC led a strike of lettuce workers at eighteen farms in the Imperial Valley, an agricultural region on the California-Mexico border and a major destination for braceros.

In 1962 Cesar Chávez started the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) by going door-to-door and talking to farm workers in central California. From the very start, his inner circle for the movement was comprised of Dolores Huerta (former schoolteacher), Fred Ross (who taught them all the art of organizing for political activism), and Cesar’s wife Helen Chávez.

The only way that things would change is if we all got together with one voice. We had to do it together.

—Helen Chávez, wife of Cesar Chávez

Three years after starting the door-to-door campaign, in 1965 Cesar Chávez had convinced 1,200 people to join his organization, but he felt the organization was too new and not adequately funded to take action . . . yet. However, later that year Filipino farm workers started a strike against conditions in the grape fields of the San Joaquin Valley. On a summer evening in 1965, Cesar met with the members of the NFWA to ask them if they were willing to join forces with the Filipino farm workers. The vote was unanimous to join the huelga (strike).

In 1965 the farm workers’ conditions were appalling. They had no bathrooms or drinking water provided in the fields. They were regularly sprayed with pesticides while working in the crops. Child labor was rampant. They were paid $1 per hour or less and had no health benefits, working very hard and long hours. And they lived in shabby homes with no hope of prosperity or security. The people who picked the food for America did not themselves have enough to eat.

From the very beginning of the strike, Cesar warned everyone that the growers were already retaliating with intimidation and violence, but that this movement would only succeed if they made a commitment to never retaliate to the growers’ violence with violence.

The first tactic used by the growers to diffuse the striking farm workers was to hire strikebreakers (called “scab labor”) from Mexico. They brought them in by the truckload, and the harvest went on. The strikers begged the strikebreakers to join the union, and many of them did. The growers however just brought in more busloads and began to play loud music so that those working in the fields could not hear the strikers share the story of what the strikebreakers coming to work in the fields meant. The growers brandished guns, shot over the heads of the strikers, and beat people up. The local police turned a blind eye to the illegal tactics of the growers, and the local government in Delano passed new laws to try to stop the strikers. They limited the number of strikers allowed in each field, made it illegal to wear a t-shirt with the NFWA logo on it, and banned the words “huelga” and “strike” from being shouted on the picket line.

All these tactics caused pressure to build among the strikers and challenged their commitment to nonviolence. Cesar was aware of Dr. Martin Luther King’s work in the Civil Rights Movement and was also studying Mahatma Gandhi. He continued to make it clear to everyone that nonviolence was paramount and called for public support to come in and assist the strike. Young people began to flood in to Delano, as well as organized labor groups, civil rights activists, and clergy, to join the picket lines.

All these tactics caused pressure to build among the strikers and challenged their commitment to nonviolence. Cesar was aware of Dr. Martin Luther King’s work in the Civil Rights Movement and was also studying Mahatma Gandhi. He continued to make it clear to everyone that nonviolence was paramount and called for public support to come in and assist the strike. Young people began to flood in to Delano, as well as organized labor groups, civil rights activists, and clergy, to join the picket lines.

Hundreds of men, women, and children were arrested for breaking the strike rules. Those arrested included farm workers, students, priests, and nuns. They all realized that the strike was not working because of the scab labor coming in to work in the fields. The organizers knew they had to try something else. Inspired by the successful bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, the farm workers decided to start their own boycott. They targeted Schnelly Industries, who owned a few vineyards and made wine from grapes grown in the San Joaquin Valley. Strikers and supporting volunteers spread out to thirteen cities to ask the American people to support the strike.

This branching out brought the strike and boycott to the attention of the U.S. Senate. They sent a U.S. Senate subcommittee to Delano, with Robert F. Kennedy at the head of it. Robert Kennedy confronted Delano officials about unwarranted arrests. He suggested that they take time during the lunch break to read the Constitution of the United States. Kennedy’s presence put the boycott and the strike on the national radar.

At this point, Cesar decided to do a Protest March from Delano to Sacramento to bring attention to the movement and to create yet another outlet for the farm workers to express their struggle for freedom and dignity. On March 17, 1966, seventy farm workers and supporting volunteers set out for the 300-mile march to Sacramento. On the first day they were screaming “Huelga” and waving flags as they walked along the freeway with loaded semi-trucks whizzing by. That first night many had blisters and sore feet, and Cesar had sprained his ankle. But they all kept marching.

The strikers decided to walk on back roads through small farming towns. At every stop they met farm workers and supporters who joined the NFWA and joined the march. The seventy swelled to hundreds of marchers. El Theatro Camposino, a farm worker theater group started by Luis Valdez, led rallies every night with theater performances, speeches, and singing.

The national media covering the march talked daily about the Schnelly Industries boycott. After eighteen days, Schnelly Industries agreed to formally recognize the NFWA. After twenty-five days of marching, on Easter Sunday of 1966, the march arrived in Sacramento. The marchers had swelled to 10,000 people. It was a high point for the farm workers who now knew that they were not alone and that they were going to make a change.

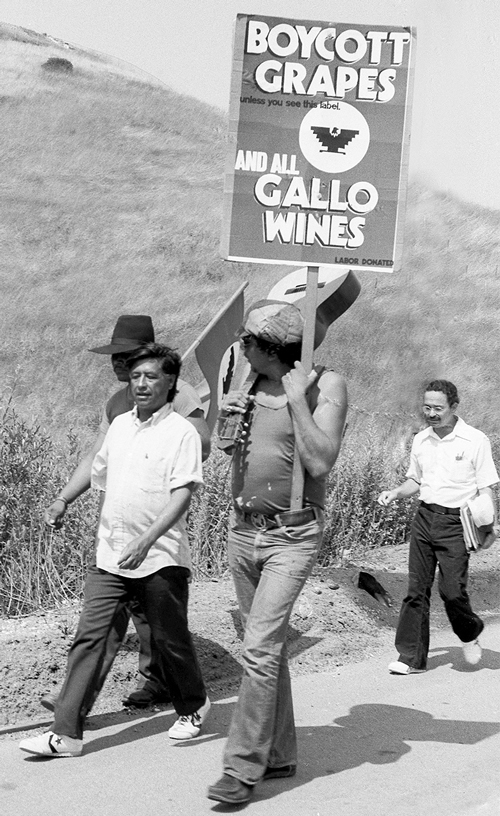

But the rest of the growers in Delano continued to resist negotiating with the NFWA. By 1967, two years into the strike, little progress had actually been made. César decided it was time to boycott Giumarra Vineyards—the world’s largest producer of table grapes. Farm workers and supporting volunteers fanned out to cities across the country to talk to people about the plight of the farm workers and to ask them to not purchase grapes from Giumarra Vineyards. These boycott organizers would travel to the city they had been assigned to with only enough money to travel there and the phone number of someone who was a union organizer or Civil Rights leader or clergy who might be willing to help them get the boycott established in their city. Giumarra Vineyards started using other growers’ labels to label their grapes in the stores. The NFWA expanded the boycott to include all grapes grown in California.

The national boycott started slowly. The strike in Delano was going nowhere. The intimidation by the growers towards the strikers continued and was escalating again. Frustration was growing, and some of the strikers wanted to resort to violence. Several water pumps and a Giumarra packing shed were burned. Cesar started a personal fast for nonviolence. Fasting is a long-standing religious tradition of making a personal statement about what is important in life. Gandhi was certainly an inspiration for Cesar to start this form of protest against the violence erupting in the movement he had started. Cesar said at this point that he would rather lose the strike than to start violence on the farm workers’ side.

The national boycott started slowly. The strike in Delano was going nowhere. The intimidation by the growers towards the strikers continued and was escalating again. Frustration was growing, and some of the strikers wanted to resort to violence. Several water pumps and a Giumarra packing shed were burned. Cesar started a personal fast for nonviolence. Fasting is a long-standing religious tradition of making a personal statement about what is important in life. Gandhi was certainly an inspiration for Cesar to start this form of protest against the violence erupting in the movement he had started. Cesar said at this point that he would rather lose the strike than to start violence on the farm workers’ side.

On the thirteenth day of the fast Cesar had to appear at the Kern County Courthouse to defend the NFWA on charges from Giumarra lawyers. When Cesar arrived, there were hundreds of farm workers lining the street. Cesar had to walk with two men supporting him in his weakness from the fast. The farm workers all knelt on their knees as he passed by and were singing “De Colores” (a popular religious song sung by activists of Mexican descent). The Kern County Courthouse was turned into a cathedral that day. Giumarra’s attorneys demanded that the judge order the removal of the farm workers. The judge replied that were he to do so it would be just another example of gringo justice and instead ordered a continuance and sent Cesar back to NFWA headquarters to continue his fast.

New members joined the struggle, and talk of violence stopped. Cesar saw that the fast was successful, and on the twenty-fifth day he ended his fast. Three thousand people came to join in a public mass to celebrate the occasion, and among them was Robert Kennedy. One week later Kennedy announced his presidential campaign, which Cesar and the rest of the farm workers supported with all their power—registering new voters and getting the word out. On June 5, Robert Kennedy won the California Democratic Primary election. At the Victory Party in Los Angeles he was shot moments after thanking Cesar and the farm workers for all their support, with Dolores Huelga by his side.

By 1969 there were boycott organizers in forty cities across the United States. They would distribute leaflets and speak to church, labor, and women’s groups about the plight of the farm workers while asking everyone to not buy grapes grown in California. They knew the American people have good hearts and would want to help if they understood what was at stake. A huge coalition of support for the boycott was built. Armies of volunteers descended on supermarkets that carried California grapes. They picketed seven days a week, twelve hours a day. In 1970 a Harris poll reported that 17 million Americans were supporting the boycott of California grapes.

The growers had lost 25 million dollars, and their grapes were rotting in the warehouses. In April 1970, a Coachella Valley grower signed a contract with the NFWA, and the first crates of grapes with the Farmworkers Union label hit the markets. The new message of the boycott was to only buy Union Label grapes. The stores selling these grapes sold out immediately and started demanding that suppliers provide more Union Label grapes.

On July 25, 1970, Cesar was contacted by Giumarra Vineyards who said they were ready to negotiate. They met that very night in a Delano motel at 4:00 A.M. Cesar told Giumarra that there would be no negotiations until all twenty-nine grape growers came to the table. It took Giumarra only twenty-four hours to get all twenty-nine growers to meet with Cesar. All twenty-nine growers signed contracts to carry the Union label on their grapes. These negotiations also won the farm workers a wage increase, toilets and cold drinking water in the fields, rest periods, pesticide controls, a medical plan, and the right to be represented by a Union. When those contracts were signed it was a victory for exploited workers all over the world.

On the day the contracts were signed Cesar said the following: “Without the help of millions who believe that nonviolence is the way to struggle, I am sure we would not be here today. Ninety-five percent of the strikers lost their homes and cars in this struggle. In losing these worldly possessions they found themselves. If you don’t give up, you will win.”

Cesar Chávez was a great man. He empowered farm workers to have dignity and self-respect through their unity and their actions. He dedicated his life to educating and serving others. He made much self-sacrifice for his cause.

The Legacy Of Cesar Chavez

In spite of the good work of Cesar Chávez and many others, the reality today is that most agricultural corporations have managed to establish their policies of greed and incredible riches for a few while the majority of the world languishes in increasing poverty. The number of Americans (from all walks of life) who do not have sufficient nutritious food to eat has increased exponentially. The rape of the earth for corporate gain is breaking down the entire ecosystem of the planet, while negativity and the pursuit of distraction permeate the consciousness of masses of people who are in denial of the severity of the situation.

In Mexico, I grew up in a cooperative farming village called an “ejido”. My mother grew up in the ejido, and my father grew up sixty miles away in Hermosillo. He was a city boy until he married my mother and began to work the four-hectare plot that my mother was entitled to when she married. The ejido is a farm where families who have become part of the cooperative have a plot of land that they can grow food and/or raise animals. People lose their allotted plot if they don’t use it. When a plot is lost to one family through disuse, it is given to another family who is an established part of the cooperative and will put the land to good use. In this way my family added to the original four hectares.

We also made many trips to the mountains to harvest food that was growing wild throughout the seasons of the year. In the 1980s I attended Agricultural Engineering School where I learned about commercial agriculture. I soon became sensitive to the many chemicals used in these agricultural programs and became disenchanted with this course of study because of the emphasis on chemical pesticides. Since then, I have been an outspoken activist against nonsustainable agriculture, which is harmful to the environment and to the workers harvesting the food, as well as to the people who eat it.

I have lived for about three decades at Avalon Gardens & EcoVillage, which is the campus for The University of Ascension Science and The Physics of Rebellion, in which I also have studied and taught these many years. I am able to apply my childhood experiences on the ejido and my education to the work I do. In the gardens I have worked and mentored others in many areas, including: plant propagation, creation of habitats for pollinators and beneficial insects, management of culinary and medicinal herb production, consultant for vegetable production, and overseeing the processing of all dairy products (such as cheeses, yogurt, butter, and kefir).

I am blessed to work with an experienced team who oversee food production and meal preparation—from seed to table—as well as the preservation and storage of our foods. I am also one of a group of educators for children and hundreds of visitors who come to Avalon Gardens to learn more about regenerative agriculture and community living. I have supervised the making of soaps, lotions and medicines from herbs grown in our gardens and continue to work with my husband and a team in designing and creating oasis garden-spots, which are watered by rain and grey water in basins and key areas within our circle-of-living cluster of community homes and buildings.

I believe that we can learn from the success of Cesar Chávez and the United Farm Workers Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Today we can apply many of the principles that he and other activists have proved to be effective. We all need to move forward into a new culture that values all life. My experiences in the ejido and at Avalon Gardens & EcoVillage have shown me that there is a way to live cooperatively and in tune with one another and the planet.

Why not take your first (or next) step towards truly safe and sustainable food production—whether it’s simply reading more to educate yourself about this vital movement worldwide or starting a window-box or backyard vegetable garden, creating a habitat for pollinator and beneficial insects, or joining a local co-op, or doing something even more activist-spirited and inspired, for we all need to become the very change that we wish to see in the world.

[i] I recommend two excellent films about Cesar Chávez. The first is a documentary titled: Viva la Causa—the Story of Cesar and A Great Movement For Social Justice, which was produced by the Southern Poverty Law Center and is part of the Learning for Justice film kit series. The second is a biographical drama (released in Spring 2014) that accurately dramatizes his story and is titled: Cesar Chávez.

photo by Cathy Murphy

photo by Cathy Murphy